The age of whaling

told through photographs

Welcome to another edition of Seascapes – a collection of incredible oceanic artwork and photography.

Let’s dive in 🎨

Hunted, harpooned, and dragged bleeding back to the shore, whales have been brutalised by the practice of whaling for hundreds of years. In the 20th century alone, almost 3 million whales were killed for their oil. Whaling was the industry of its day, with whale oil once in high demand for its use in lamps, lubrication, soap, textiles, varnish, explosives and paint. In more modern times, whales are still hunted for their meat — for dogs mainly, but some humans still eat it too.

Whaling is barbaric and cruel, and is very much of a time that should have long since passed. However, something can be two things at once and old photographs (and some new) of the mighty whale slumped at the doors of these whaling stations are worth looking back on. Some I’ve chosen for the visceral emotions they’re bound to conjure, others for the fascinating stories behind them. As a collective, I hope these photographs serve as a reminder that we do not own the Earth1, we belong to it.

*Warning graphic content*

#1

1912.

Whalers on South Georgia's shores are dwarfed by their massive catch - likely a southern right whale. These gentle giants, named for being the 'right' whales to hunt due to their slow speed and buoyancy when killed, were pushed to the brink of extinction. After 300 years, commercial whaling was eventually banned in South Georgia and several breeding populations of the southern right whale recovered, others did not.

#2

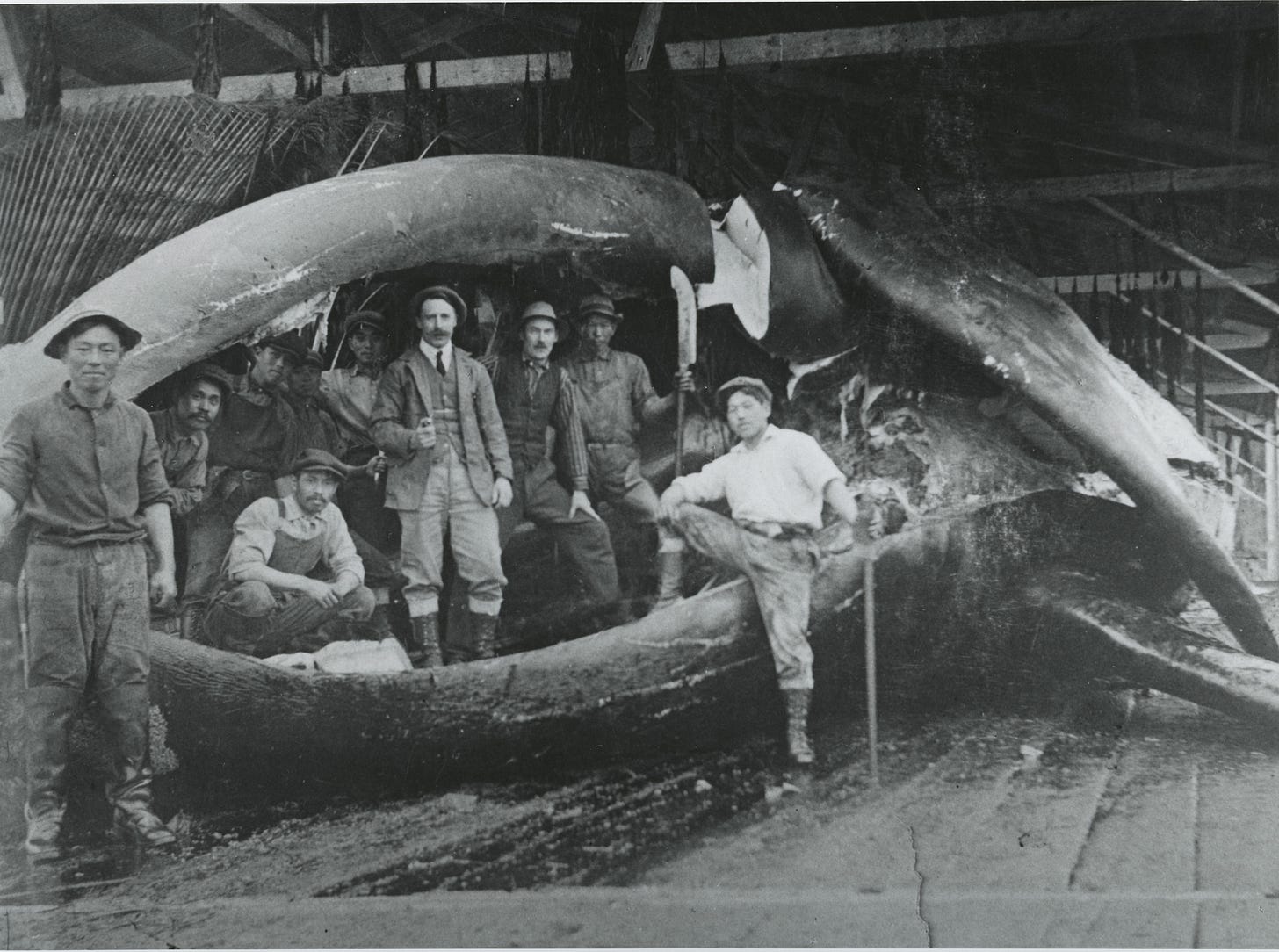

1915.

A group of men pose atop their massive catch at the Akutan whaling station — the sole such facility in the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. Built by the Pacific Whaling Company in 1912, this station processed countless whales until its closure in 1939. The photograph was captured by John Nathan Cobb — a prominent fisheries biologist and later editor of the Pacific Fisherman, who took many of the whaling photographs in and around this region.

#3

This is a stark image of an industry in its twilight years. Taken in the late 1950s or early 60s, it depicts workers at Coal Harbour’s whaling station preparing to flense2 a blue whale. Coal Harbour is nestled in a small bay on Vancouver Island and was one of North America's last and most prolific shore-based whaling stations. Its unique geography made it an ideal location for the industry as the 50-kilometre sound acted as a natural funnel, guiding migrating whales from the open ocean directly towards the waiting whalers. Across just two decades, this station was responsible for processing almost half of the 25,000 whales killed in British Columbia waters.

#4

The Petrel, now beached at Grytviken in South Georgia, is a gritty relic of the whaling industry. Built in 1928, this vessel spent over three decades hunting whales in Antarctic waters before being adapted in 1957 to harvest seals from the beaches where they raised their young.

Grytviken itself holds a significant place in maritime history as it is closely associated with the legendary explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton. It was here that Shackleton orchestrated the rescue of his stranded Endurance crew following the ill-fated expedition. Tragically, Shackleton met his own end in Grytviken when he returned on another expedition.

#5

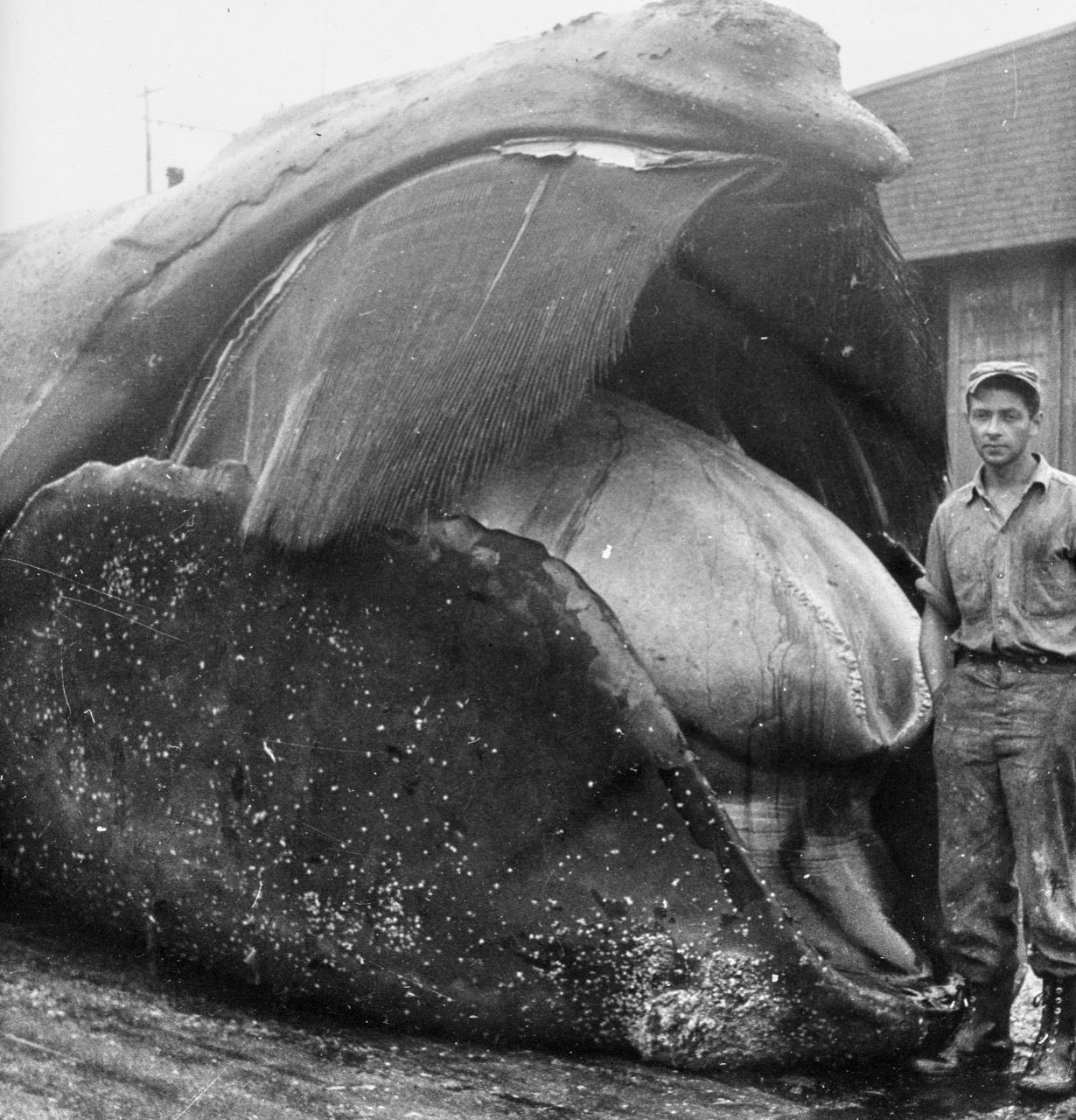

1951.

Gordon Pike, a biologist with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, stands beside a North Pacific right whale at the Coal Harbour whaling station. This photograph captures the grim reality of whaling as it documents the last right whale seen in British Columbia waters for over six decades. From 2013 to 2021 there were only four confirmed sightings of right whales off the coast of BC, highlighting how close these whales came to extinction.

#6

1947.

This photograph shows Faroe Islanders watching as men pile up pilot whale carcasses from a recent ‘grind’. The Grindadráp, as it’s known in Faroese, is a type of drive hunting that involves herding cetaceans, primarily pilot whales, into shallow bays where they’re separated from their family, beached, and then butchered. While the Faroese often defend this practice as a thousand-year-old tradition, the brutal reality is that nearly 1,000 cetaceans are slaughtered annually for no real purpose as their meat is too toxic to eat in large quantities. Regardless of why they do it, the Grindadráp remains a cruel and unnecessary mass killing.

#7

The old and rusting oil tanks and processing facilities of the abandoned whaling station at Grytviken.

By the 1960s, relentless hunting had decimated whale populations around South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, making whaling economically unviable. Grytviken closed its doors, as did many other stations in the area, and so the bay is now littered with rusting ships and industrial relics. These facilities were a key part of the brutal process of ‘flensing’ and ‘trying out’ ( if the whale had been caught close to shore) — where whale blubber was stripped and boiled to extract oil. For those caught further out to sea, the ‘trying out’ was done aboard the ship using a trywork (a built-in furnace) while the carcass was discarded overboard.

#8

1920.

This photograph shows workers processing a whale at the Rose Harbour whaling station in Haida Gwaii, otherwise known as the Queen Charlotte Islands. Established in 1910 by the Queen Charlotte Whaling Company, Rose Harbour operated until its closure in 1943. So popular was the area for whaling that between 1916 and 1919, Vancouver filmmaker A.D. Kean produced a silent black and white documentary on the industry titled ‘Whaling: British Columbia’s Least Known and Most Romantic Industry’.

Ironically, despite once being a centre for whaling, Vancouver would later become a hub for environmental activism. New Zealand neuroscientist, Paul Spong, became a local leading voice opposing commercial whaling and it’s here that Greenpeace initially took up their cause.

#9

This photograph captures a diver examining a corroded anchor, one of the few remains of the 19th-century Nantucket whale ship, Two Brothers. Captained by George Pollard, whose previous vessel Essex was famously rammed and sunk by a sperm whale, the Two Brothers met its end on the French Frigate Shoals in 1823. The wreck, discovered in 2008 by marine archaeologists working for NOAA, ended Pollard’s whaling career. Before its ill-fated final voyage, the ship had returned from the Pacific in 1821 with a staggering 1,231 barrels of sperm oil and 158 barrels of whale oil.

#10

Another from the Coal Harbour whaling station, this photograph shows workers processing a freshly-caught whale. Crew from this facility caught a variety of large whale species, including sperm, blue, fin, and sei whales, in addition to the humpback pictured here.

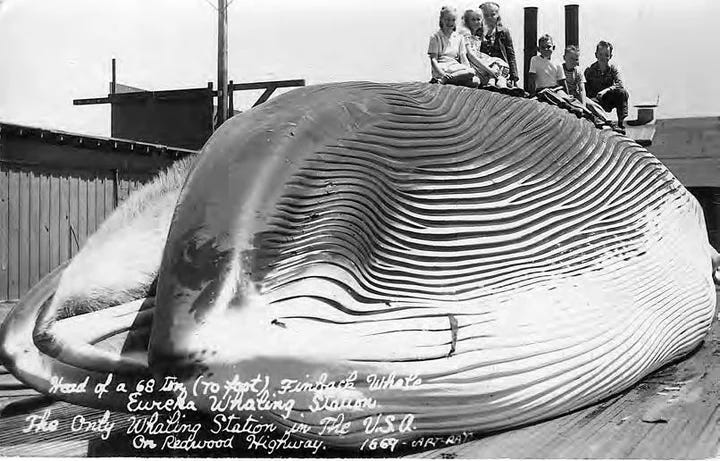

#11

In the 1920s, Eureka, where this photo was taken, was part of a network of whaling stations along the Californian coast. An extensive history on whaling in the area is covered here, and tales from a whaling plant union member can also be read here. It’s among these that I found this photograph with the caption: “Children sit atop a finback whale at Fields Landing. The view is of the finback’s head and undersides. The whale’s mouth is open and the baleen plates of the upper jaw are clearly visible.”

#12

The cabin Bamsebu surrounded by piles of beluga whale bones at Ingebrigtsenbukta, a bay in Svalbard's Sør-Spitsbergen National Park. In 1930, a whaling station was established here, but the site now represents the last remaining beluga whaling station in Svalbard, with all cultural remains officially protected. Some 50 years ago an estimate of 550 individual skeletons were counted on the beached but thankfully beluga whales are now protected in Svalbard’s waters. However, it is worth noting that Norway continues to hunt minke whales.

#13

Two dead Antarctic minke whales killed in the Southern Ocean hang by their tails from a Japanese whaling ship. Despite centuries of whaling and its devastating impact, some countries persist in this outdated and cruel practice. In 2019, Japan left the International Whaling Commission, abandoning the pretence of ‘scientific research’ and openly resumed commercial whaling. Since then they’ve truly dug their heels in: they spent tens of millions on a new whaling ‘mothership’, expanded their commercial whaling target list to include fin whales — a species still considered vulnerable by the IUCN, and recently succeeded in harpooning the first fin whale in half a century.

#14

At first glance this scene might appear similar to the industrial whaling witnessed above, but it tells a much different, more nuanced story. Taken under three feet of pack ice in Tasiilaq, Greenland, the image shows diver Anna Von Boetticher among 20 whale carcasses in an area known locally as ‘flenseplassen’ or ‘skinning grounds’.

Unlike commercial whaling operations, this site represents a carefully regulated, community-based hunting practice. Each year, Inuit hunters catch only a few whales from the area’s stable population, adhering to strict quotas.

After the community has used the meat and blubber, the remaining carcass is returned to the shallows where small sea creatures continue the cycle of life similar to how they would if a natural ‘whale fall’ [link - scheduled for 18th November] had occurred.

Here at Beached we are building a community that can put our brains and resources together to highlight and fund solutions to the problems facing the whales and the oceans they live. I hope you’ll join our humble community and click subscribe for free or support our work by purchasing the paid subscription.

All Beached posts are free to read but if you can we ask you to support our work through a paid subscription. These directly support the work of Beached and allow us to engage in more conversations with experts in the field of marine conservation and spend more time researching a wider breadth of topics for the newsletters. Paid subscriptions allow us to dedicate more time and effort to creating a community and provide the space for stakeholders to come together, stay abreast of each other’s work and foster improved collaboration and coordination.

One day Beached hope to donate a large percentage of the revenue from paid subscriptions to marine conservation organisations and charities to support their work too. Working together, we can reverse the degradation of our oceans.

Amie 🐋

Or any of it’s creatures.

Strip the skin and fat from the carcass.

I want to read this but feel I need to brace myself first.

I can’t quite articulate why, but I find that shot of “The Petrel” especially haunting… All of these images, though… -shudders-