The jellyfish has existed for over 500 million years.

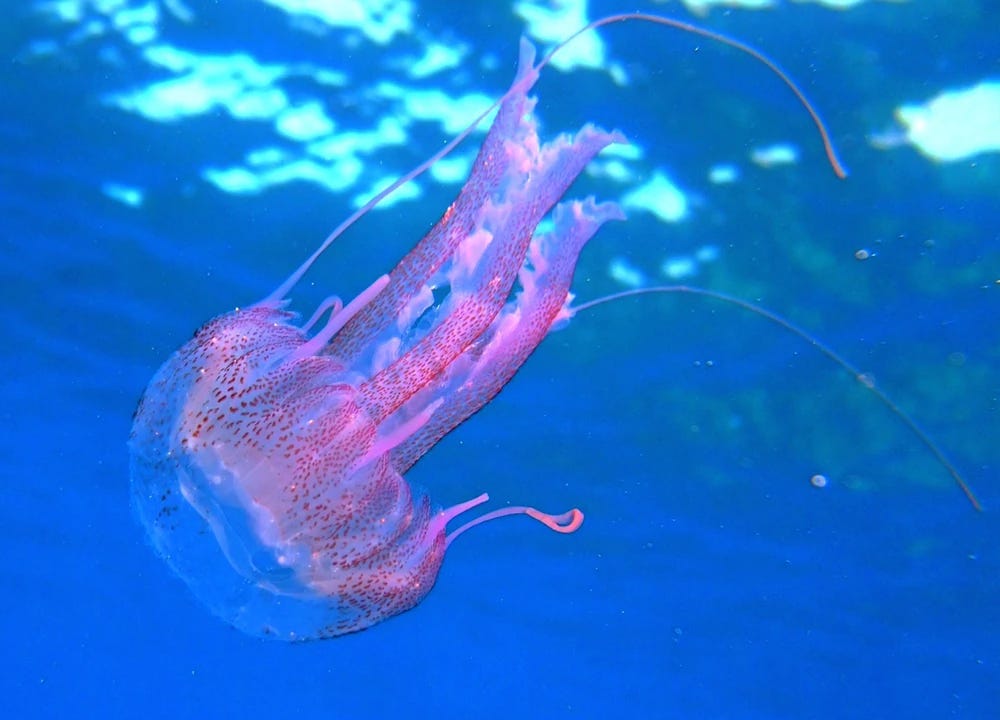

They have no heart, no brain, no lungs, and no bones, just muscles and a nervous system drifting on the currents of every ocean across the world. Their bodies, made of more than 95% water, have a central mouth which they use to feed on phytoplankton. Some are smaller than the naked eye can see. Others have tentacles longer than a blue whale. Some have stings strong enough to kill a human. Others can go back in time by reversing their own life cycle. Some look like a fried egg. Others glow in the dark. One type of jellyfish is believed to have eyes and can see colours and shapes. Over 2000 species have been discovered and identified so far, but scientists believe there could be as many as 300,000. And who knows what party tricks those unknown jellies might have. Jellyfish have existed for over 500 million years and there’s a good chance they’ll still be here in another 500 million.

As climate change steadily warms the planet, consistently breaching the 1.5°C tipping point, up to a million species of plants and animals are at risk of extinction. Unless something changes immediately, warming and increasingly acidic oceans, pollution and habitat loss will continue to catastrophically impact the natural world, on an unprecedented scale. And yet, though most living beings will suffer immensely from the effects of climate change, it is a small comfort to know that the jellyfish will not. Jellyfish thrive in warm, fertiliser-rich, deoxygenated ocean water. Must be nice.

They actually enjoy these conditions so much that jellyfish populations have risen in as many as 68 ecosystems around the world since 1950, and counting. And, from October 2022 to September 2023 sightings increased by 32% compared to the previous year. There are many positives to an abundance of jellies as they provide great services for us and for the oceans. As a mobile-habitat they keep crabs and fish safe from predators within their tentacles. This provides nursery grounds and transportation for any juvenile or small creatures. Also, their place near the base of the food chain makes them excellent ecosystem engineers and they’re a vital food source for turtles, fish, seabirds and whales.

As the lowly phytoplankton makes up a good portion of a jellyfish’s diet, the carbon these phytoplankton absorb becomes locked away in a jellyfish's non-existent belly and will sink to the ocean floor when they die. This makes jellyfish great carbon sinks too! In a similar fashion to whales, jellyfish recycle essential nutrients moving up and down the water column and as they drift across the sea.

However, it turns out you can have too much of a good thing. While Beached would usually celebrate a flourishing marine species, things can get a little out of control with jellyfish. Known as ‘jellyfish blooms’, ocean or wind patterns cause masses of jellyfish to swarm in a certain area. As populations thrive in the warming waters these blooms have previously led to clogging power plant pipes, causing power outages, overcrowding fishing nets and forcing beach closures.

So how exactly is climate change allowing jellyfish to thrive and why might this be a bad thing?

Recent research has shown that as the burning of fossil fuel heats up the planet, over 90% of that excess heat is absorbed by the oceans. This leads to a more acidic and less oxygenated marine space. While most species such as coral reefs cannot survive these rapid changes, jellyfish thrive in the higher temperatures as their embryos and larvae develop more quickly. Faster reproduction rates cause the already prolific jellies to spawn in their millions – the Atlantic sea nettle can spawn 45,000 eggs per day. There’s also more room for jellyfish to grow as coral reefs die off.

Ecosystem disruption on this scale can wipe out entire species from a region. Where jellyfish blooms occur they overfeed, which in turn creates a monoculture within the ecosystem and the plankton they consume is depleted for other species.

Jellyfish blooms, sometimes referred to as a smack of jellyfish, are also highly destructive as they emerge in their thousands. What was once a rare occurrence now happens frequently across the world, affecting tourism, the fisheries sector, and even nuclear power plants. Several months ago, an influx of jellyfish on Spain’s north-east coast led to an increase of 41% for stings needing medical attention compared to the previous year. In 2018, over 1000 people were stung in just one week in Florida. The UK and Sweden have had to perform costly closures of their nuclear underwater cooling systems as they became blocked by jellyfish swarms. On a salmon farm in the Western Isles of Scotland, 300,000 salmon were killed when hundreds of tiny ‘mauve stinger’ jellyfish got inside the cages and significantly reduced the amount of oxygen in the water. Jellyfish swarms spell trouble at the best of times but in these new conditions, courtesy of climate change, they are out of control.

It may sound silly but it is important to remember that this is not the jellyfish’s fault. They are just very much enjoying the conditions we’ve been creating for them. It’s not just our burning of fossil fuels that’s giving the jellyfish a helping hand either. As we overfish, killing turtles and sharks in the process, we are removing the jellyfish’s natural predators from the water. Our man-made coastal constructions of harbours, marinas, boat docks and piers are ideal for polyps1. Polyps permanently attach themselves to hard surfaces and release tiny, juvenile jellyfish who drift away into the open sea. They have a preference for man-made rather than natural surfaces and so as our coastal construction grows, so do they. Jellyfish also benefit from fertiliser runoff. This occurs when fertiliser from the land enters the water system, eventually making its way to sea. Its properties cause the oversaturation of water with nutrients which leads to an excess of algal growth. As this algal decays it depletes the water of oxygen and you guessed it – the jellyfish love it2. Meanwhile the other fish suffocate and die.

Can anything be done?

Well, if jellyfish are thriving off the effects of climate change then maybe we should start there. I won’t repeat what we’ve all heard before but a move away from fossil fuels, eating less red meat, and tackling deforestation might just do the trick. In the meantime, we could use this abundance of jellyfish to our advantage.

The GoJelly project, funded by the EU, is developing research which could see the mucus of jellyfish used to bind microplastics. This would act as a filter in wastewater treatment plants and in factories where microplastics are produced. Stopping these tiny particles from getting further into the water system and out into the oceans prevents harm to marine ecosystems and wildlife. Another idea is to use excess jellyfish as fertiliser for aquaculture feeds. Fish farms are currently fed with captured wild fish which only worsens the overfishing issue. This method would be much more sustainable and keep natural fish stocks at a healthy level. If you have spotted any interesting jellyfish species in your local area, record the sightings here or here and contribute to marine research.

As it stands, a warming ocean will only lead to more jellyfish. As long as their food source survives there’s no slowing them down just yet.

Here at Beached we are building a community that can put our brains and resources together to highlight and fund solutions to the problems facing the oceans and its inhabitants. I hope you’ll join our humble community and click subscribe for free or support our work by purchasing the paid subscription.

All Beached posts are free to read but if you can we ask you to support our work through a paid subscription. These directly support the work of Beached and allow us to engage in more conversations with experts in the field of marine conservation and spend more time researching a wider breadth of topics for the newsletters. Paid subscriptions allow us to dedicate more time and effort to creating a community and provide the space for stakeholders to come together, stay abreast of each other’s work and foster improved collaboration and coordination.

One day Beached hope to donate a large percentage of the revenue from paid subscriptions to marine conservation organisations and charities to support their work too. Working together, we can reverse the degradation of our oceans.

Amie 🐋

Think of polyps as the Queen Bee who stays at home.

Maybe the jellyfish cut a deal with some oil giant, fossil fuel-burning, monoculture farming CEO type.

I’m on board with the theory of a back room deal with an oil company...jellyfish have always looked shady to me😎

Jellyfish and party tricks in the same sentence :) love it!