Earlier this year, I wrote about the critical role of marine protected areas (MPAs) in safeguarding our ocean. These underwater havens have the potential to be at the frontline in preserving the biodiversity, resources, ecosystem services, cultural heritage, and fragile habitats of our ocean. But – and it's a big 'but' – I also raised concerns about the rise of 'paper parks': MPAs that exist solely on paper rather than in practice.

With the global goal of protecting 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030 just a few years away, the number of MPAs is growing rapidly as local, national and international governments and organisations push to reach the target. As of right now, just 8% of the ocean is under some form of protection so this upscale in effort should be well received and yet, the quality of many MPAs is so poor that the ocean might be better off without them.

Let’s not get confused – every bit of ocean protection is a step in the right direction, but for MPAs to truly work their magic, they need robust management, proper enforcement, and total restrictions on harmful activities. Otherwise, we risk creating a false sense of security while our marine ecosystems continue to struggle.

Recent announcements

Since April, when I last wrote about MPAs, there has been a flurry of announcements worldwide. And as encouraging as it is to see a step up in ocean conservation efforts, many seem to lack the teeth needed for effective protection. Which makes me nervous to think of the direction we’re headed in a bid to save our seas.

However, some of the more promising plans include; Canada's Tang.ɢwan · ḥačxʷiqak · Tsig̱is MPA. This vast area protects 133,017 km² of hydrothermal vents and seamounts off Vancouver Island, which is a mighty 93% of Canada's known seamounts – all to be co-managed by several First Nations. The MPA is built to safeguard the unique features of the seabed and creatures like sea lilies and basket stars who live there. Restrictions include the prohibition of bottom-contact fishing and dumping and the protection of ancient coral forests and glass sponges. These decisions were made following the advice of an Offshore Pacific Advisory Committee which included representation from multiple local interests. The collaborative approach with First Nations and the clear restrictions on damaging activities are promising, however, the sheer size of the area may present challenges for effective monitoring and enforcement.

Uruguay has also taken steps towards marine protection around Isla de Lobos. While smaller than Canada's effort, it's a significant move for a country that previously had less than 1% of its waters under protection. The island is home to one of South America's largest sea lion colonies, and the MPA directly aims to protect them1 and other marine life in the area. Restrictions on overfishing and other extractive practices are in the works, but, as always, the devil will be in the details of implementation.

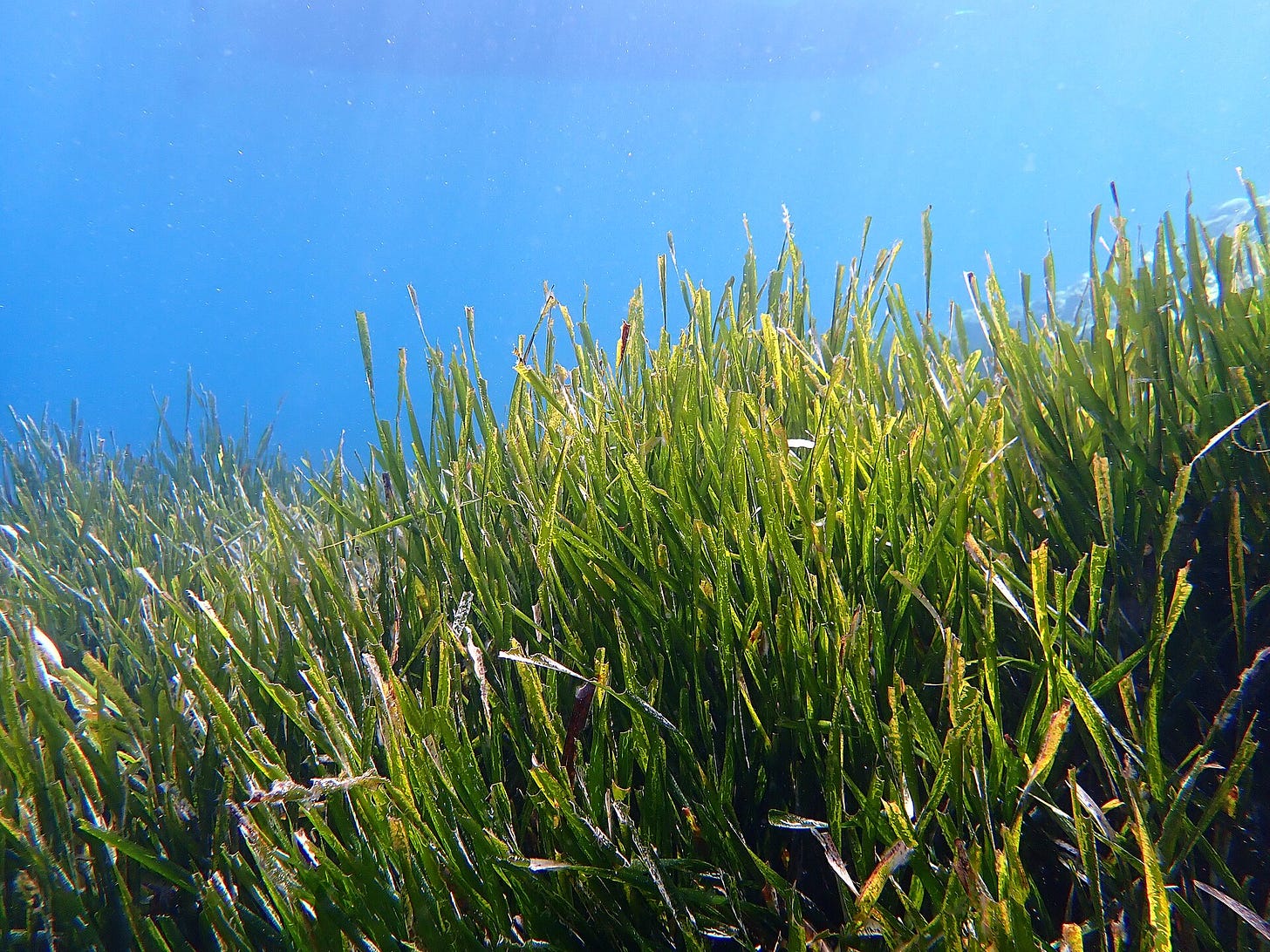

Italy has recently expanded its Asinara National Park MPA from 10,800 hectares to a whopping 66,000 hectares. The management plan here looks promising, with new measures for small-scale fishing based on scientific data, monitoring and tagging of species like lobster, and even the creation of a quality brand for sustainably caught local fish. It's encouraging to see this integration of science and local fishing practices, and support from Fondazione Capellino and the Blue Marine Foundation should help with consistent enforcement and regular assessment.

Harsh reality

While these recent announcements paint a hopeful picture, a sobering study on MPAs in Europe reveals the truth about their effectiveness. Research published in the One Earth journal shows that a staggering 86% of MPAs in the EU provide only "marginal" protection against industrial activities such as dredging, mining, and bottom trawling. Which begs the question; what exactly are these marine protected areas protected from?

It’s quite confounding, so let’s digest this one more time: the vast majority of areas supposedly set aside for marine conservation are still open to some of the most destructive practices threatening our ocean.

This revelation sets us way back, putting us in the very early stages of actually protecting our ocean. It even calls into question the global target of 30% protection by 2030. If we’re striving to achieve 30x30 just to say we’ve achieved it, then we need to go back to the beginning and start again. 30% protection was determined by scientists and policymakers2 as the minimum area needed to effectively conserve biodiversity and ecosystem functions. This isn't just about quantity – it's about quality, connectivity, and genuine protection.

10% of our ocean is supposed to be under "strict" protection by 2030 but faux protective measures won’t get us anywhere close. The study concluded that reaching these “strict” protection targets will require "radical changes" to how activities in MPAs are regulated.

The root of the problem, according to the researchers, lies in the "flexible" nature of EU directives. This flexibility allows for far too much wiggle room when it comes to truly protecting these areas. While some countries like Slovenia do well at keeping destructive activities at bay, and the Mediterranean and Baltic Seas show higher levels of "strong protection", these are exceptions rather than the rule.

The challenge lies in the lack of legally binding regulations across the EU which puts the onus on individual regions or countries to do something. Greece has taken a pioneering step by becoming the first country to ban bottom trawling in their MPAs earlier this year, with Sweden following suit. However, these isolated actions highlight the need for a more cohesive, EU-wide approach to truly effective marine protection.

Antarctic ambitions

We also mustn't forget the protection needed in our ocean that lies beyond national jurisdictions. The Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica is a prime example of how we benefit from protecting the ocean – it serves as a massive carbon sink, drives ocean circulation patterns, and harbours incredibly biodiverse life critical to marine ecosystems worldwide.

The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) is set to meet next month to discuss the creation of a large-scale MPA in the Antarctic Peninsula – one of four proposals for MPAs in the Southern Ocean. If all are agreed upon, this could protect 26% of the Southern Ocean – nearly 3% of the global ocean – and would be the largest act of ocean conservation in history.

However, progress has been frustratingly slow. Despite the clear ecological importance of these waters, political disagreements have stalled the creation of new Antarctic MPAs. This situation underscores the complexity of establishing truly effective protected areas, especially in international waters.

Without robust management and proper enforcement, we risk creating nothing more than 'paper parks' – marine reserves protected in name only, while marine ecosystems continue to suffer. We must ensure we're not just ticking boxes, but creating genuinely protected areas that can withstand the pressures of our changing world.

Here at Beached we are building a community that can put our brains and resources together to highlight and fund solutions to the problems facing the ocean. I hope you’ll join our humble community and click subscribe for free or support our work by purchasing the paid subscription.

All Beached posts are free to read but if you can we ask you to support our work through a paid subscription. These directly support the work of Beached and allow us to engage in more conversations with experts in the field of marine conservation and spend more time researching a wider breadth of topics for the newsletters. Paid subscriptions allow us to dedicate more time and effort to creating a community and provide the space for stakeholders to come together, stay abreast of each other’s work and foster improved collaboration and coordination.

One day Beached hope to donate a large percentage of the revenue from paid subscriptions to marine conservation organisations and charities to support their work too. Working together, we can reverse the degradation of our ocean.

Amie 🐋

Sea lions were once incessantly hunted, with an estimated half a million slaughtered between 1873 and 1949. They were given a lifeline when a ban was enforced in 1991.

As part of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

Thanks for calling out a serious flaw which can be found in ordinances or regulations. Namely, how to enforce. A small, local example for me is our nearby beach ordinance prohibiting dogs. Owners don’t always clean up after them and, if not on a leash, they can disrupt shore birds, sea turtle nests and other wildlife. Yet there is little enforcement. The haughty, defensive responses I receive if I happen to say something to offenders makes me want to go vigilante! Your essay is aimed, of course, at a more expansive, critical issue of our oceans. Thanks for shining a spotlight.

Really great topic to bring up. Something hopeful to add to the monitoring discussion is the use of Distributed Acoustic Sensing, which allows for up to 100km lengths of fiber optics to be used to measure vibrations on the sea floor. This is already in place for underwater cable monitoring to ensure that anyone anchoring or trawling nearby will be warned before snagging the cable.

I am hopeful that as this technology is integrated into ocean science more that it will lead to a better bottom monitoring system.