In past epochs, mass extinctions were solely brought about by a significant force of nature. Animals disappeared because the planet had rapidly changed – either from a volcanic eruption, temperatures plummeting, oceans turning increasingly acidic and losing oxygen, or, all of the above. Life simply couldn’t evolve fast enough to survive these major changes.

Species like the megalodon ruled the seas for 13 million years until the end of the Pliocene when global cooling and a collapse at the base of the food chain caused a cascade of extinctions. By 3.6 million years ago, it was gone1. Scientists believe that the die-off of organisms at the base of the food chain led to a domino effect of a third of all large marine animals going extinct, including 43% of turtle species and 35% of seabirds.

The Perucetus, one of the heaviest animals to ever live, most likely vanished during the Eocene–Oligocene extinction, otherwise known as the Grande Coupure2. This enormous climate shift marked the beginning of permanent ice sheet coverage on Antarctica and unsurprisingly the suddenly cool temperatures also kick-started an Ice Age3.

Even more catastrophic was the Permian–Triassic extinction – Earth’s largest extinction event. So severe, it’s thought to have annihilated 83% of the planet’s genuses, 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species, and is also the largest known mass extinction of insects. Scientists believed it was triggered by intense volcanic activity in the Siberian Traps, when vast amounts of CO₂ were released into the atmosphere thus dramatically depleting ocean oxygen levels. It wiped out around 96% of marine species, including the spiral-jawed Helicoprion. Even the deep ocean4 was affected, with some areas void of any oxygen at all, meaning vital organisms at the base of the food chain disappeared, once again leading to a total collapse of the food chain.

The five mass extinction events each left their mark on the planet, effectively resetting the evolutionary path of life each time. Some species survived, most didn’t. It was all down to climate, time, and a little bit of luck.

Now, extinction has a human face. We’re responsible for an average 73% decline in wildlife populations in the last 50 years alone. From 1970-2020, WWF’s Living Planet Report 2024 asserts that freshwater populations fell by 85%, terrestrial species by 69%, and marine life, 56%. The Holocene extinction5 is the name given to the ongoing collapse of biodiversity, driven by human activities such as overfishing, habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change.

Long have we been warned about the consequences of biodiversity loss, of the dangers of a planet stripped of wildlife and the ecosystems it relies on. Not least, a world without other beings to share it with.

Some species are clinging on; the Vaquita, North Atlantic right whales, and the Hawaiian monk seal. Others are already gone, like the Bramble Cay melomys – the first officially recognised mammalian extinction due to anthropogenic climate change.

Here are just a few of the ocean animals from the Holocene that humans have, in one way or another, driven to extinction:

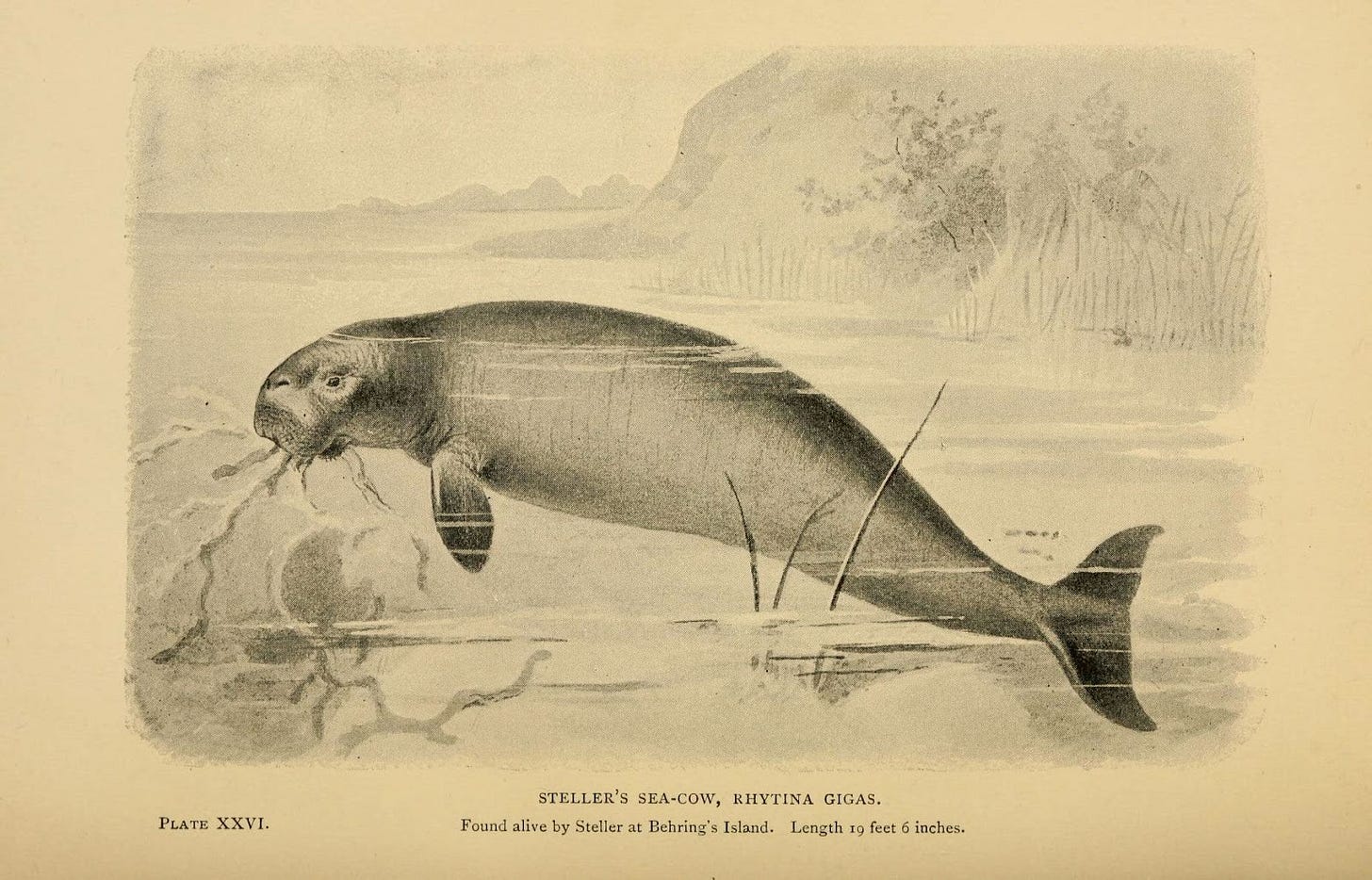

Steller’s Sea Cow

First described by Georg Wilhelm Steller in 1741, Steller’s sea cow lived in the icy waters of the Bering Sea, grazing on kelp in shallow bays around the Commander Islands. A gentle giant, it grew up to 10 metres long and weighed as much as 11 tonnes, which is even bigger than many modern whales. Unlike its tropical sirenian relatives (Dugongidae), the dugong, it had adapted to sub-Arctic life, but its slow movements made it easy prey. Hunted heavily for meat, fat, and hide, Steller’s sea cow was wiped out just 27 years after first contact with Europeans.

Chatham Crested Penguin

Thought to have gone extinct sometime between 1650 and 1700, this crested penguin once waddled along the shores of New Zealand’s remote Chatham Islands. Discovered only from subfossil bones, it vanished within 200 years of the arrival of Polynesians — likely hunted or outcompeted for food. The Chatham penguin was officially recognised as a distinct species in 2019 and named Eudyptes warhami after penguin biologist John Warham. Some believe it may have survived until 1872, as a crested penguin from the Chatham islands was rumoured to be held in captivity for several weeks, whether or not that’s true, these birds are long gone now.

Caribbean Monk Seal

Once found lounging on beaches and rocky shores across the Caribbean, these seals lived on a diet of fish, lobsters, and squid. Christopher Columbus referred to them in 1494, describing eight “sea wolves” his crew killed while they slept on the sand. Hunted for their blubber and meat, and likely pushed to the brink by prey loss from overfishing as well, the Caribbean monk seal was last seen in 1952. But it wasn’t until 2008 that it was officially declared extinct. Its two closest relatives — the Mediterranean and Hawaiian monk seals — are also both considered vulnerable and critically endangered.

Great Auk

The great auk was a flightless seabird but powerful swimmer once found ranging across the North Atlantic, breeding on remote rocky islands. It was hunted for centuries for its meat, oil, and feathers, and was also a victim to collectors paying a hefty price for its eggs. First appearing around 400,000 years ago, they were a food source for Neanderthals and what’s believed to be their image is carved into the walls of the El Pendo Cave in Camargo, Spain, and Paglicci, Italy from more than 35,000 years ago.

Despite early attempts to protect them — including an 18th-century law in parts of Canada that saw violators publicly flogged — global demand only increased. When their last safe breeding site was lost to a volcanic eruption in 1830, the surviving birds were pushed onto ground more accessible to humans and by 1835 fewer than 50 remained. The last known pair was killed in 1844 while incubating an egg — collected on request for a private merchant who wanted specimens. A species that once numbered in their millions, and had lasted for hundreds of thousands of years, was gone in just a few short decades.

Baiji

Native to China’s Yangtze River, the baiji was a freshwater dolphin. It’s likely the first cetacean driven to extinction by human activity and the first global extinction of an aquatic vertebrate in over 50 years since the demise of the Japanese sea lion and the Caribbean monk seal in the 50s. As industrial use of the river for fishing, transportation, and hydroelectricity increased, the baiji’s numbers collapsed. Despite a government-backed conservation plan, a 2006 expedition found no trace of the species. It hasn’t been seen in over 20 years and is now listed by the IUCN as Critically Endangered: Possibly Extinct.

Japanese Sea Lion

The Japanese sea lion was once frequently found along the coasts of Japan and Korea, but particularly in the Sea of Okhotsk and the Sea of Japan, where it bred on flat, sandy beaches and rocky shores. It was hunted throughout the 1900s for food, oil, and traditional medicine leading to their demise. Though once considered a subspecies of the California sea lion, they were only recognised as a distinct species in 2003 despite the divergence point between the two species occurring around 2 million years ago. The last confirmed sighting was in 1974.

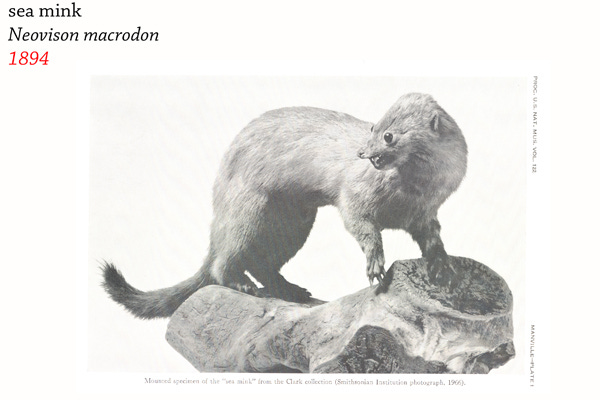

Sea Mink

The sea mink lived along the shores of New England and the Gulf of Maine, where it made its home in coastal caves and crevices. Larger and more marine-oriented than its cousin, the American mink, it was highly prized by fur traders and hunted relentlessly for its pelt until the species disappeared in the early 1900s. It was only formally described in 1903 — after it was already extinct.

Here at Beached we are building a community that can put our brains and resources together to highlight and fund solutions to the problems facing all marine species. I hope you’ll join our humble community and click subscribe for free or support our work by purchasing the paid subscription.

All Beached posts are free to read but if you can we ask you to support our work through a paid subscription. These directly support the work of Beached and allow us to engage in more conversations with experts in the field of marine conservation and spend more time researching a wider breadth of topics for the newsletters. Paid subscriptions allow us to dedicate more time and effort to creating a community and provide the space for stakeholders to come together, stay abreast of each other’s work and foster improved collaboration and coordination.

One day Beached hope to donate a large percentage of the revenue from paid subscriptions to marine conservation organisations and charities to support their work too. Working together, we can reverse the degradation of our oceans.

Amie 🐋

If you’re looking for something to be grateful for today, let it be that we never had to share a planet with the megalodon.

French for ‘great cut’.

The Late Cenozoic Ice Age.

We must never underestimate the importance of life in the deep-sea to the functioning of our planet.

Otherwise known as the Anthropocene extinction or the sixth mass extinction.

I have a big tattoo on my calf of the Great Auk, because its story is so tragic. I still want to occupy my whole bottom leg with animals that humans drove to extinction, so that I can commemorate the short-sightedness of man while also allowing the animals to take on a slightly longer life (as long as I exist). This article is awesome!

This is a very beautiful tribute to these remarkable beings. Thanks Amie- I enjoy learning about anything to do with ocean life, even sad news.