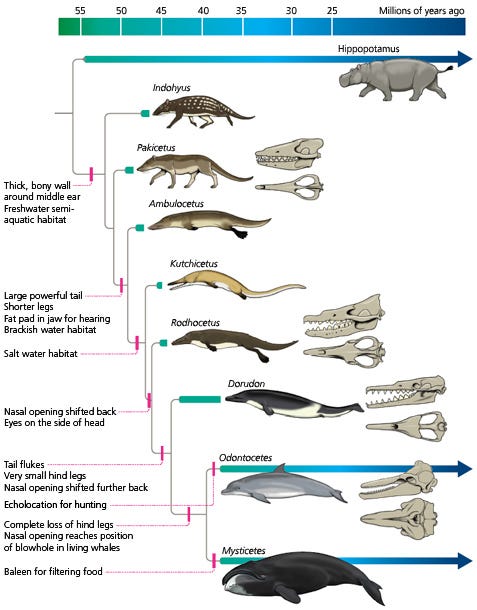

400 million years ago, when the ancestor of all four-limbed creatures took its first steps on land, it seemed implausible that 350 million years later, one of its descendants would do a full one-eighty and return to life aquatic. And yet, the Pakicetus, and others, did exactly that.

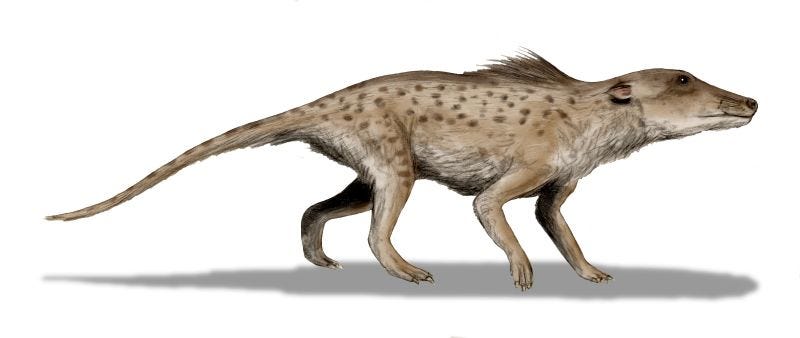

Pakicetus, a land mammal, was essentially the first whale.

Beginning as dwellers of the earth, they waded back into the water and within 8-10 million years (the quickest of blinks in geological terms) became masters of the ocean. An ear bone is what first led scientists to link the Pakicetus (which is very much a land mammal in appearance) to whales, as they discovered their heads had the long skull shape of a whale. Closer inspection uncovered a part of the inner ear which strongly resembled that of living whales and is unlike any other mammals.

But this wasn’t the only clue that led scientists to believe whales were once land mammals. After all, they breathe air, their flippers are made up of five ‘finger’ bones, they nurse their young with their own milk, and whale embryos have small back ‘legs’ which disappear before they’re born. There are, of course, several other early whale species identified by experts as such but most have anatomy that suggests they lived an aquatic lifestyle and so the connection is more obvious.

For the Pakicetus, and similar land mammals, the story goes that these ungulates were partial to eating plants at the water’s edge and with the additional benefit of hiding from danger in the shallow water, they began to spend so much time there that their bodies eventually adapted to swimming. Front legs became flippers. Blubber replaced fur for warmth and streamlined swimming. The nostrils moved to the top of their heads for easier breathing. Their tails grew to be strong and powerful, replacing their back legs. And some even grew baleen to filter feed as their diets and hunting methods changed.

The evolutionary mutations necessary to turn from land mammal to ocean native were extensive, but ran much deeper than just physical appearance. Internal modifications like altering the function of the lungs, saliva and blood are a must for breathing underwater, but as these changes aren’t obvious in fossils, scientists had to study the DNA of whales to uncover this genetic progress.

What they found was one particular genetic gain which allowed these early whale species to live a successful life at sea. This gene carries instructions for myoglobin - a protein that supplies oxygen to the cells in muscles - which is particularly useful to all diving vertebrates and mammals. Most diving animals have a positive charge within their myoglobin which makes the cells repel one another like magnets. Research suggests that this prevents the proteins from sticking together and so the animals are able to maintain high concentrations of oxygen to support their dives.

But for this one essential gene early whales acquired during the evolutionary process, they lost far more, perhaps because it was detrimental to their new life as a cetacean or it was a case of ‘use it or lose it’.

Scientist Michael Hiller and his colleagues conducted a study which compared the genomes of four cetaceans - dolphin, orca, minke, and sperm whale - with 55 land mammals as well as a manatee, a walrus and a Weddell seal and found that a grand total of 85 genes had become nonfunctional in cetaceans when their ancestors settled into a life at sea.

Among the genes lost were those associated with blood clot formation. As mammals have lungs and need air to breathe, diving for extended periods without oxygen can be dangerous. To reduce the risk and conserve oxygen, cetaceans decrease the amount of blood flowing to the extremities of their body meaning the blood vessels in these areas are constricted. However, this increases the likelihood of blood clots. To avoid this dilemma and make it less likely that blood clots would form, the genes of early whales were simply (probably not that simple) inactivated. As they no longer work, cetaceans are free to dive for longer without the risk of blood clots.

Cetaceans also no longer possess a gene which produces saliva, which I bet you’d never given any thought to, but it makes total sense — why would they need it?

In a slightly more surprising turn, the sense of smell is also greatly reduced in cetaceans. Scientists observed as much as an 80% reduction in genes needed for smelling among toothed whales, as well as a reduction for taste. Early whales had many receptors which helped them to determine smells but these worked for odours in the air, not the water. This is different to a shark's sensory system, which cetaceans do not possess, and so their olfactory receptor genes were no longer useful and were eventually ‘phased out’.

The evolution of whales - completed around 40 million years ago - has seen them remain relatively unchanged, in stark contrast to Homo sapiens who evolved just 200,000 - 300,000 years ago. And yet, despite our brief tenure but supposed great intelligence, we face the crisis of regressing, threatening the very balance of life in our oceans that we are so intrinsically linked to. Reflecting on the incredible evolutionary journey of whales from land to sea, it’s important to remember that for all of the fortunes of their past, their future now rests in our hands.

Here at Beached we are building a community that can put our brains and resources together to highlight and fund solutions to the problems facing the Pakicetus’ descendants. I hope you’ll join our humble community and click subscribe for free or support our work by purchasing the paid subscription.

All Beached posts are free to read but if you can we ask you to support our work through a paid subscription. These directly support the work of Beached and allow us to engage in more conversations with experts in the field of marine conservation and spend more time researching a wider breadth of topics for the newsletters. Paid subscriptions allow us to dedicate more time and effort to creating a community and provide the space for stakeholders to come together, stay abreast of each other’s work and foster improved collaboration and coordination.

One day Beached hope to donate a large percentage of the revenue from paid subscriptions to marine conservation organisations and charities to support their work too. Working together, we can reverse the degradation of our oceans and rivers.

Amie 🐋

Nitpick:

"why would they need it? "

No. The question is "what pressure cause them to not make it."

The answer is obvious.

It gives an aquatic ape hope that one day, only millions of years away, we too will have fins, that is if we survive our insane industrial mega-death tech.

Key perspective regarding cetaceans & the ocean: the large whales, dolphins & orcas were ruling the oceans when our primate ancestors were still swinging from trees. Hominids are a very recent mutation, like neo-natal aliens invading their ocean dimension. Stealing all the herring & salmon & other wicked industrial pathology. Running over everything with our gigantic smoke-belching vessels.

If this planet belongs to any highly sentient beings by precedence, it is the cetaceans.

Maybe the alien diplomats from Alpha Centari or Zeta Reticuli will enlighten us, or maybe they will harpoon us & suck our brain oil. Cosmic toss up with our current planetary karma...