Sharks are essentially living fossils, having glided through the Earth’s oceans for over 400 million years already. They have outlasted the dinosaurs and have survived mass extinction events to become one of the most successful and enduring groups of animals on the planet.

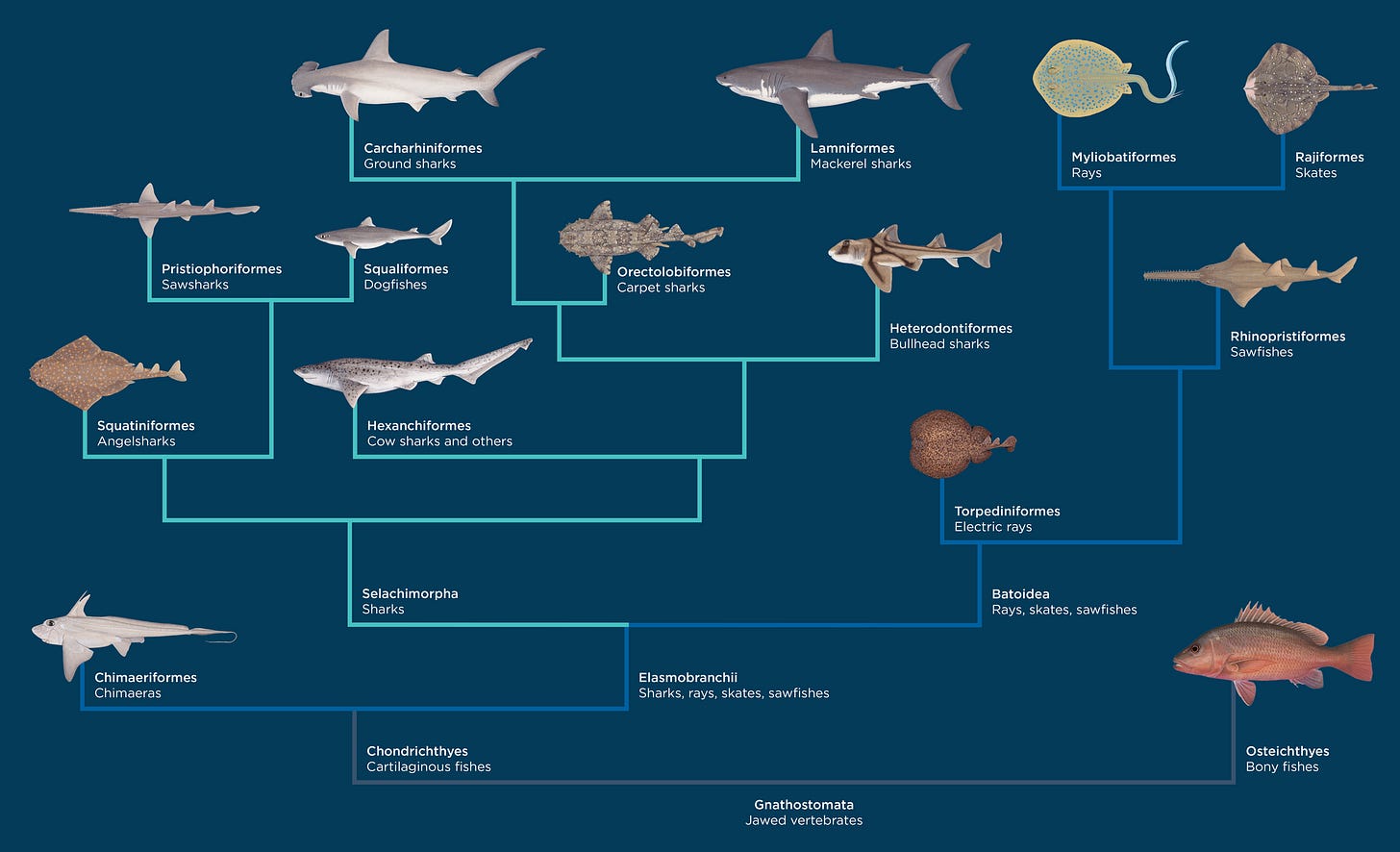

Throughout their long history, the Elasmobranchii subclass, aka cartilaginous fish, has evolved into a diverse array of species, from whale sharks and great whites, to their close relatives: rays and skates.1

And while whales are far removed from the original form of their ancestor, the Pakicetus (which was actually a land animal) sharks haven’t changed all that much. They have been swimming the seas long before any animal even stepped foot on land. But what exactly did they evolve from and how have they survived for so long?

Basal lineage

Sharks have dominated the top of the marine food chain for hundreds of millions of years, surviving alongside fearsome marine reptiles like Mosasaurs and Plesiosaurs. Fossil records paint a vivid picture of shark evolution, revealing species from over 150 mya that are remarkably similar to those swimming in our oceans today.

But pinpointing the exact root of sharkdom is complex given their remarkable longevity. It's thought that they descended from a small leaf-shaped fish that had no eyes, fins or bones. These primitive fish then evolved into the two main groups of fish seen today: bony fish (Osteichthyes) and cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes – the sharks, skates, rays and chimaera). Some researchers suggest that the earliest direct ancestor for the cartilaginous group is the small and spiny acanthodians, with their bony skeleton being the most significant change in the species between now and then.

The first ‘true shark’

One of the earliest known species of ‘shark’ was the Cladoselache. This ancient creature lived around 380 mya and offers great insights into shark evolution. Their fish-like head, seven gills (as opposed to the usual five), and long but less muscular body are the main features which set them apart from sharks we see now. They also lack dermal denticles which gives sharks their sandpaper-like skin, instead having thin, fragile skin. However, one similar trait they have to some modern species, such as the megamouth shark and frilled shark, is their mouth was located at the front of its snout.

The earliest fossil evidence of any shark-like creature came around 70 million years before2 the Cladoselache showed up, so giving it a title of ‘first shark’ isn’t quite right. In fact, the Cladoselache might not be a shark at all. It might actually be related to an extinct fish called symmoriiforms – highlighting the complexity of the shark family tree.

If this is all sounding a bit dubious, it's worth remembering that scientists are working with evidence drawn from 450-million-year-old scales - a significant challenge that leaves plenty of margin for error.

Sharks through the ages

These studied scales from the early Silurian period are essentially the beginning of the story for sharks but here’s a bitesize version of what has happened since:

The Paleozoic Era (545-250 mya)

The earliest shark-like teeth are from around 410 mya and introduce us to the Doliodus problematicus, otherwise known as the ‘least shark-like shark’. This is believed to be a transitional species, bridging the evolutionary gap between acanthodians and sharks.

Not long after (if you haven’t already realised by now, ‘not long’ means a few million years) the Cladoselache shows up - marking the appearance of the first recognisably shark-like creature despite most likely being a chimaera rather than a shark3.

As Earth hit the Carboniferous Period some 359 mya, the oceans entered the ‘golden age of sharks’.

A mass extinction event had killed off at least 75% of all species on Earth including many large fish. This gave sharks the opportunity to evolve into all kinds of wacky shapes and sizes. This includes the Stethacanthus with its anvil-shaped dorsal fin, the Helicoprion with a saw-like bottom jaw, and the Falcatus, the males of which had long spines protruding from their back and over their head.

The Mesozoic Era (250-65 mya)

Yet another mass extinction had wiped out 96% of marine life at the start of the Mesozoic Era. But not the shark.

Around 150 mya, while dinosaurs continued to roam on land, sharks were mastering the oceans. They developed flexible, protruding jaws to gulp down larger prey and sharpened their swimming skills.

Their continuous survival allowed many species to continue adapting in wonderful ways, some small, some much larger with serrated teeth to help them feed on large fish and marine reptiles.

Another mass extinction ensued towards the end of the Cretaceous period – the one that killed the dinosaurs.

The Cenozoic Era (65 mya - present day)

This put smaller sharks at the top of the food chain as the larger species had vanished.

They shared the seas with whales and little else to threaten them. That is until we move closer to the present day…

Origin of particular species

The last 66 mya on Earth has nurtured the evolution of some of the most impressive shark species in history, many of which are very familiar to us today. It saw the emergence of Otodus obliquus, the ancestor to Otodus megalodon. O. megalodon grew to be one of the largest sharks in history, reaching up to 18 metres in length and scientists consider it to have been one of the most powerful predators too with teeth measuring 17cm long.

Contrary to popular belief, O. megalodon was not related to great white sharks but rather in competition with their ancestors. Great whites evolved during the Middle Eocene (45 mya) from broad-toothed mako sharks.

Hammerhead sharks appeared between 50 and 35 mya, making them one of the youngest groups of sharks. Their distinctive head shape is believed to aid in electroreception for hunting prey, and may also improve their vision, swimming, and sense of smell.

One of the most recent additions to the shark family tree is the genus Hemiscyllium, known as walking sharks. These sharks are still evolving in western New Guinea, providing a rare glimpse of 'evolution in action' as they use their fins to walk’ along the seabed. It would be the stuff of nightmares if they weren’t so small and harmless. For now, that is…

The importance of fossils

The majority of what we know about prehistoric sharks comes from their fossilised teeth, which have provided scientists with a wealth of information about these ancient predators.

Shark teeth are common fossils found in marine rocks worldwide. After death, a shark's cartilaginous skeleton rots away, usually leaving only teeth, dermal denticles, and fin spines as fossils. Shark teeth are made of dentin, a material harder than bone, increasing their fossilisation chances. Sharks continuously produce new teeth, potentially generating 20,000 to 40,000 in a lifetime.

The fossil record documents over 3,000 shark species, though many more likely existed. These remains, especially teeth, provide crucial information about a shark's diet, species, and environment.

To sum up

Sharks' remarkable journey across the ages showcases their resilience and adaptability. These ancient creatures have weathered global catastrophes for hundreds of millions of years, their basic design remaining largely unchanged throughout.

However, their longevity makes their current plight all the more devastating. Despite surviving events that reshaped our entire planet, sharks now face their greatest challenge: us. Bycatch, overfishing, habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change pose unprecedented threats. And their negative perception further complicates conservation efforts.

It would be a tragic irony if, after enduring so much and for so long, sharks were to succumb to the actions of a species that has existed for merely a fraction of their tenure on Earth.

Cover image by Gerald Schombs

Here at Beached we are building a community that can put our brains and resources together to highlight and fund solutions to the problems facing sharks. I hope you’ll join our humble community and click subscribe for free or support our work by purchasing the paid subscription.

All Beached posts are free to read but if you can we ask you to support our work through a paid subscription. These directly support the work of Beached and allow us to engage in more conversations with experts in the field of marine conservation and spend more time researching a wider breadth of topics for the newsletters. Paid subscriptions allow us to dedicate more time and effort to creating a community and provide the space for stakeholders to come together, stay abreast of each other’s work and foster improved collaboration and coordination.

One day Beached hope to donate a large percentage of the revenue from paid subscriptions to marine conservation organisations and charities to support their work too. Working together, we can reverse the degradation of our oceans and rivers.

Amie 🐋

Despite being in the same class, molecular evidence suggests chimaeras split away from the main shark and ray lineage around 420 million years ago (mya) – showing how little these species have changed since then in comparison to other species, e.g. the whale. Chimaeras are in the subclass Holocephali.

Dermal denticles, or skin scales, were found in Colorado but scientists are still unsure whether these came from true shark ancestors or just shark-like animals.

Confused yet?

Your pic of the sharks teeth/ray plates etc sent me back to family vacations to a group of rustic cabins on a cliff overlooking Chesapeake Bay. We kids spent countless hours finding sharks teeth and other fossils. Calvert Marine Museum was a short drive and we would study their exhibits and compare them what we found that week. Thanks for reminding me of happy times, Amie!

I'm a big fan of animal research and I didn't know about your newsletter. Having discovered it was a wonderful surprise!

Apart from the fact that I was captured by the intro '...those who call it (the ocean) home', but I can't wait to read the issues already published and discover the new ones. I imagine you have already written a lot on the topic, but there is great fervor regarding the developments in research on octopuses and their cognitive abilities. One of the books that captured me 'Other Minds' by Peter Godfrey-Smith.