If you thought you were having a tough week, imagine being a krill. An average day in the life involves endlessly dodging the largest mouth on Earth, avoiding countless other predators, and somehow finding time to save the planet through their surprisingly impactful faeces. Not bad for a creature the size of your thumb.

The lowly krill might be near the bottom of the food chain, but they're central to a flourishing ocean. Around 85 species live in seas across the world, feeding and fuelling marine ecosystems everywhere. Their consumption of phytoplankton (which absorb CO₂ and release oxygen) and their top spot in the diet of hundreds of animals means they're a great ally in our fight against climate change.

Though their populations are nowhere near what they used to be, there are around 700 trillion of these shrimp-like individuals still bobbing about in the big blue. The female's ability to lay 10,000 eggs at a time helps explain this impressive number, and the fact that they can lay several times during a spawning season.

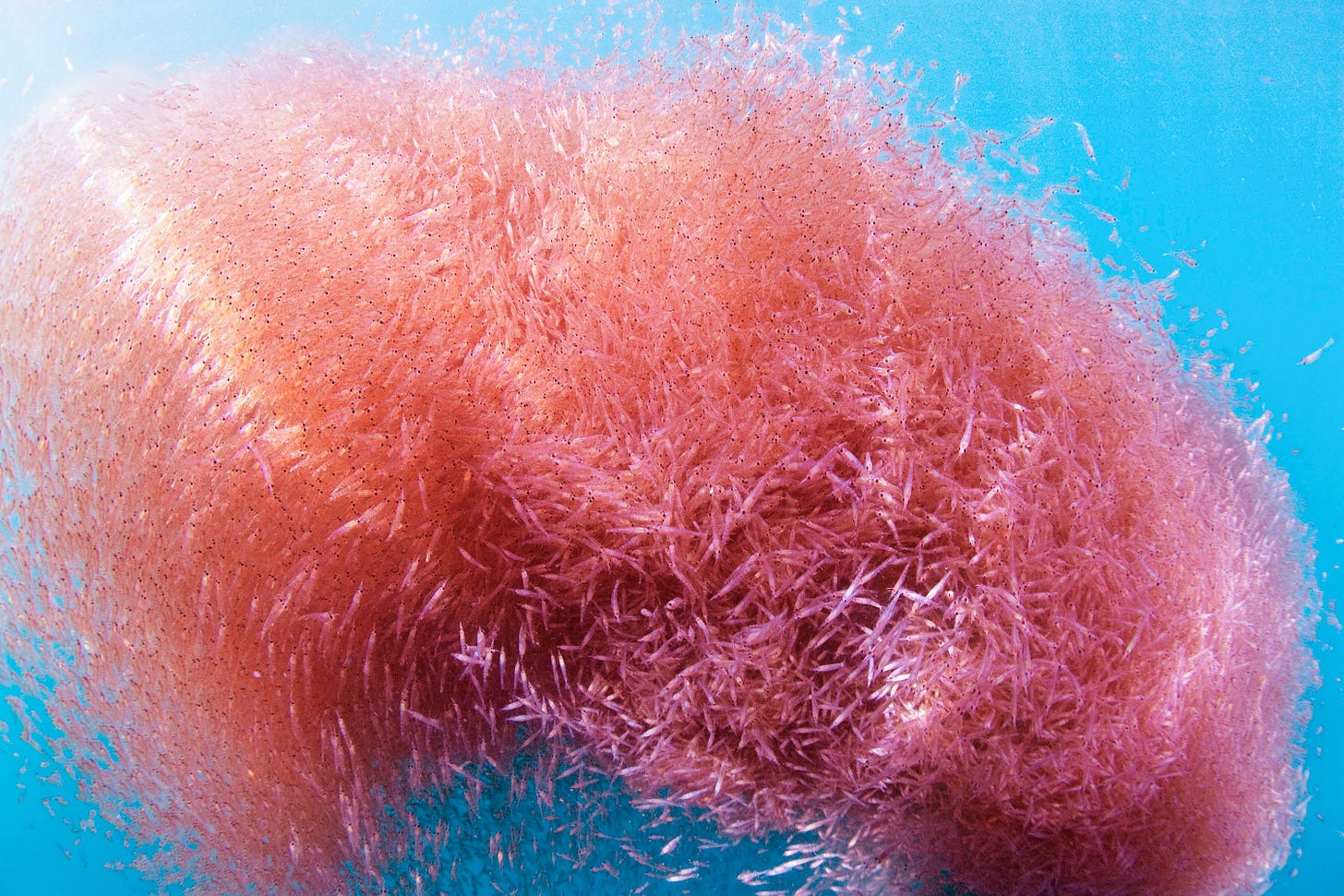

If they manage to avoid being the dinner of a whale, seal, penguin, seabird, squid or fish, krill can survive for 6-10 years depending on the species. They're the main source of sustenance for the world's largest animal, the blue whale, who eat around six tonnes of krill every day. They're an easy target too, as they typically live at the surface of the ocean feasting on phytoplankton and using swarming as a defence mechanism against predators. I'm not so sure this is working out for them though.

Considering they only grow to around 6 cm in length, they show remarkable intelligence. Taking part in what is known as 'vertical migration', most krill choose to spend their days conserving energy and avoiding predators within the water column but at great depths. When krill consume the carbon-rich phytoplankton at the surface of the water, they release this in the form of carbon and nutrient-rich faecal pellets, which studies show – for the Antarctic krill alone – removes up to 12 billion tonnes of carbon from the atmosphere every year. That is one productive poo! As a full stomach equates to a decline in swimming activity for krill (I'm sure we can all relate), they sink blissfully to the seabed, well-fed and ready for a nap. The carbon-rich faecal pellets they produce on the way sink with them and are thus stored away in the seabed.

Their huge biomass (just one Southern Ocean species makes up around 379,000,000 tonnes of biomass) means this sequestering happens on a massive scale.

Sadly, krill populations have declined by 80% in the last 50 years. This is largely attributed to a loss of ice cover caused by climate change. Antarctic krill eat ice-algae as their primary food source, so the ice loss has a huge impact on their population.

The remarkable interdependence of nature unfortunately means the population decline of even one small species has disastrous consequences on the entire ecosystem, especially a species who proactively fights climate change like krill do. Without ocean biology, atmospheric CO₂ levels would be 50% higher than they are today.

Just this month, a crucial meeting that could have secured vital protections for krill ended in disappointment. CCAMLR-43, the annual gathering of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (quite the mouthful, I know), took place in Hobart, Tasmania.

Two major proposals were on the table:

A revised krill fishery management plan to better protect these crucial creatures.

A new Marine Protected Area (MPA) in the Antarctic Peninsula – an area that's warming at twice the global average.

Both proposals were voted down.

The timing couldn't be worse. While world leaders gather at COP16 in Colombia, championing their commitment to protect 30% of the ocean by 2030, CCAMLR – who could have actually helped achieve this goal – has taken a step backwards. Though scientists and conservationists were hopeful that at least one of the four proposed MPAs would be secured this year, CCAMLR hasn't adopted a new MPA since 2016.

"The two big crises on the planet are biodiversity and climate, and the one place to take concrete action on both is at CCAMLR. This is where we have to show we are serious." says Andrea Kavanagh, Director of Pew Charitable Trusts.

This is particularly concerning given recent studies suggesting current krill biomass can't sustain both commercial fishing demands in the Southern Ocean and the needs of recovering whale populations. With key protective measures now reversed, the future of Antarctic krill – and all the species that depend on them – looks increasingly uncertain.

Some protective measures do exist, like the NOAA Fisheries Service rule prohibiting krill harvesting within 200 nautical miles off the US West Coast, but much more needs to be done. The fishing industry continues to harvest krill for aquaculture, animal feed, and supplements, while supermarkets continue to stock krill-based products despite mounting evidence of the damage this causes to Antarctic ecosystems.

David Attenborough once defined nature as the lifeblood of our society. In the same manner, I believe krill are the lifeblood of our oceans. Is that not worth protecting?

Here at Beached we are building a community that can put our brains and resources together to highlight and fund solutions to the problems facing krill and the oceans they live in. I hope you’ll join our humble community and click subscribe for free or support our work by purchasing the paid subscription.

All Beached posts are free to read but if you can we ask you to support our work through a paid subscription. These directly support the work of Beached and allow us to engage in more conversations with experts in the field of marine conservation and spend more time researching a wider breadth of topics for the newsletters. Paid subscriptions allow us to dedicate more time and effort to creating a community and provide the space for stakeholders to come together, stay abreast of each other’s work and foster improved collaboration and coordination.

One day Beached hope to donate a large percentage of the revenue from paid subscriptions to marine conservation organisations and charities to support their work too. Working together, we can reverse the degradation of our oceans.

Amie 🐋

So informative, thank you. I have known about krill as food for whales and other species since school, but realize I didn't know much about THEM at all, not even their size.

Let’s hear it for the little guys!!