You can’t enter scientific discourse with a name like ‘colossus’ and not cause the blue whale to quake in its boots just a little.

The Perucetus colossus, an approximately 39 million year old early whale species, very briefly stole first place prize from the blue whale, as the heaviest animal to have ever lived.

The first part of its name comes from its geographical origin - ‘Peru’. ‘Cetus’ comes from the Latin word for whale, while ‘kolossus’ is ancient Greek for large statue. The study which announced the Perucetus colossus as the heaviest whale ever claimed it weighed almost two times more than the blue whale's 180 tonnes, at a whopping 340 tonnes. The estimates given did range widely between 85 and 340 tonnes, but contesting the mighty blue whales’ long-held record isn’t taken lightly.

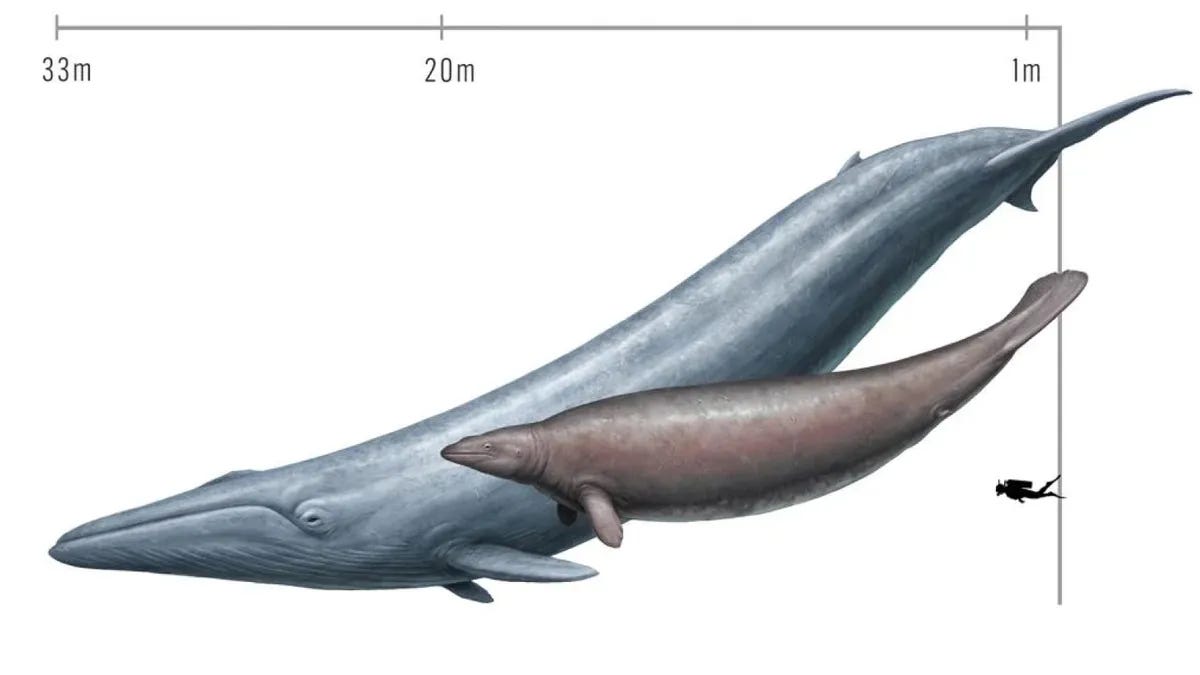

Scientists conducted the study using a partial skeleton found in the Peruvian desert over ten years ago. This skeleton consisted of 13 vertebrae, four ribs, and one hip bone placing it at 17 to 20 metres (55.8 to 65.6 feet) long. That would make it at least 5 metres shorter than the blue whale but the Perucetus’s skeletal mass was still up for debate.

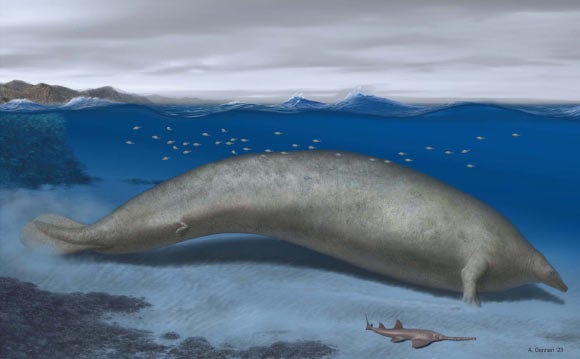

Using the structure of the skeleton, scientists were able to find some answers. Unlike modern whales, the Perucetus had extremely dense and compact bones - leading to the suggestion that it weighed more than the current heaviest animal on the planet, our blue friend. This trait is shared with sirenians like manatees and dugongs but is absent in living cetaceans. It’s been suggested that this hefty skeleton acted as a ballast, helping the animal to maintain stability in shallow, agitated coastal waters.

The heftiness likely means the Perucetus moved quite slowly and in an undulatory and anguilliform swimming style, meaning its body flexed in wave-like motions from its head to its tail. Though its diet can only be guessed at, its ancient coastal habitat suggests crustaceans and molluscs living on the seabed were a preferred meal.

But what about the record? Well, such bold claims invited scrutiny and a reassessment. As the original study lacked the Perucetus’s skull or teeth, it relied heavily on estimates from the partial remains. Dr Eli Amson, the scientists leading the team, admitted in Nature: "Figuring out body weight for an extinct species is really, really hard. We don't really know how to put meat on bone for them".

And so, a subsequent study, published in PeerJ this year, challenged the initial weight estimates. Researchers argued that if Perucetus were as heavy as the upper estimate of 340 tonnes suggested, it would have been too dense to stay afloat. Their revised calculations placed Perucetus at a more modest 60 to 130 tonnes, which is notably lighter than the blue whale's impressive 180 tonnes. Two scientists, Dr Ryosuke Motani and Dr Nicholas Pyenson, created 3D models to compare Perucetus with modern blue whales. Their findings suggest Perucetus weighed between 55 and 65 tonnes, closer to a modern sperm whale.

Despite the downward correction, Perucetus remains an extraordinary find. Its unusually dense bones, closer to that of a manatee than a modern whale, suggest an animal adapted for coastal waters rather than the open ocean. This challenges previous assumptions about where gigantic marine animals lived during the Eocene period.

So, although Perucetus cannot claim the title of heaviest animal ever, it is still a strong contender for the most intriguing. As Dr Amson notes, "This is an exceptional new species that changes our understanding of cetacean evolution".

Here at Beached we are building a community that can put our brains and resources together to highlight and fund solutions to the problems facing the descendants of the Perucetus colossus, and the oceans they live in. I hope you’ll join our humble community and click subscribe for free or support our work by purchasing the paid subscription.

All Beached posts are free to read but if you can we ask you to support our work through a paid subscription. These directly support the work of Beached and allow us to engage in more conversations with experts in the field of marine conservation and spend more time researching a wider breadth of topics for the newsletters. Paid subscriptions allow us to dedicate more time and effort to creating a community and provide the space for stakeholders to come together, stay abreast of each other’s work and foster improved collaboration and coordination.

One day Beached hope to donate a large percentage of the revenue from paid subscriptions to marine conservation organisations and charities to support their work too. Working together, we can reverse the degradation of our oceans.

Amie 🐋

Do researchers have any definitive thoughts as to if this animal was also a mammal?