“I am a nice shark, not a mindless eating machine”

- Bruce, Finding Nemo

In my research for Beached every week, I spend hours scouring the internet for some positive news on the wellbeing of different marine species. I read up on the latest technologies designed to clean up our oceans. I look for any recent policy changes aimed at reducing shipping vessel collisions, or innovation within the fisheries sector to combat the rate of entanglements. I often scroll through countless humpback whale breaching videos too, and friendly beluga whale interactions, and killer whales sneaking up on kayakers. So I can understand why the Instagram algorithm thinks I want to see any and all ocean inhabitants, including the shark. And I do. Sort of.

I want to learn that shark populations are thriving, that their prey is abundant, their waters clear of poisonous debris, their skin free of any entanglement scars, and their stomachs full of tasty fish (and not plastic). But for all my well wishes I’m not sure I definitely need to see a video of a shark emerging out of the murky deep with my own eyes.

Since my whale watching experience several years ago when my fondness for whales grew, I have become a lot less afraid of sharks. As a child I developed a great fear of them and couldn’t even bear to look at a photograph of one. Their rows of razor blade teeth, lifeless eyes and ominous slinking through the water made me incredibly nervous. I at times avoided swimming in the sea, petrified of the unpredictability of what I assumed were bloodthirsty predators out to attack.

Admittedly, my fear was derived from a wildly inaccurate source with a ridiculous plotline (Deep Blue Sea) and I now see that my fear of sharks is heavily misplaced. I understand how misunderstood the shark really is because of their reputation as something to be scared of when in reality they kill fewer people than cows each year. We’re told we should be scared of sharks so we are. Granted, their scary mouths and tendency to bite people occasionally doesn’t help, but does that mean they deserve to die in their millions every year?

The beauty of connecting with one marine creature is the lessons learnt about other marine animals. I can now see that to fear sharks is for the most part, irrational. I recognise how truly vulnerable the shark has become as we humans show ourselves to be the real monsters in how little we value their lives.

All marine creatures face threats from multiple anthropogenic sources but it seems that the general dislike of sharks and their negative portrayal as the villain, the monster out to get us, a danger that could attack at any moment, has allowed the shark fin trade to continue without consequence.

What is the shark fin trade?

The shark fin trade kills more than 100 million sharks globally every year. Caught intentionally, as bycatch, legally, and illegally, it has led to a 71% decline in shark populations in the last 50 years.

While overfishing also contributes to this decline, shark finning is uniquely barbaric. It involves hauling a shark on board where its fins will be removed and carcass dumped overboard. The sharks, who are often alive when all of this happens, will be left to drown or be eaten as its body sinks to the ocean floor. The savageness of this act and rate at which it happens across the world, is horrifying. And by taking only the fins, fisheries can save on space and increase profits.

Not all shark finning happens in this way. In at least a third of countries shark finning of this kind is illegal on sustainability and animal welfare grounds. Small-scale fishers will partake in shark fishing where the entire animal carcass is caught, landed and exported legally for its meat as well as its fins. ‘Fin to carcass ratios’ is another method which allows fisheries to remove fins at sea and store them separately to the carcass but both must be retained.

However, due to the corruption within fisheries involved in the trade, lines blur and captains have been found to store smaller carcasses with larger fins that don’t match up. The system is abused to such an extent that poorly paid deckhands (who sometimes spend years at sea on obscenely long contracts) are being dragged into dangerous, illegal work while captains increase their profits from the excess catch. Both sharks and humans suffer on these boats as human trafficking and other human rights abuses are often perpetrated on the shark finning vessels.

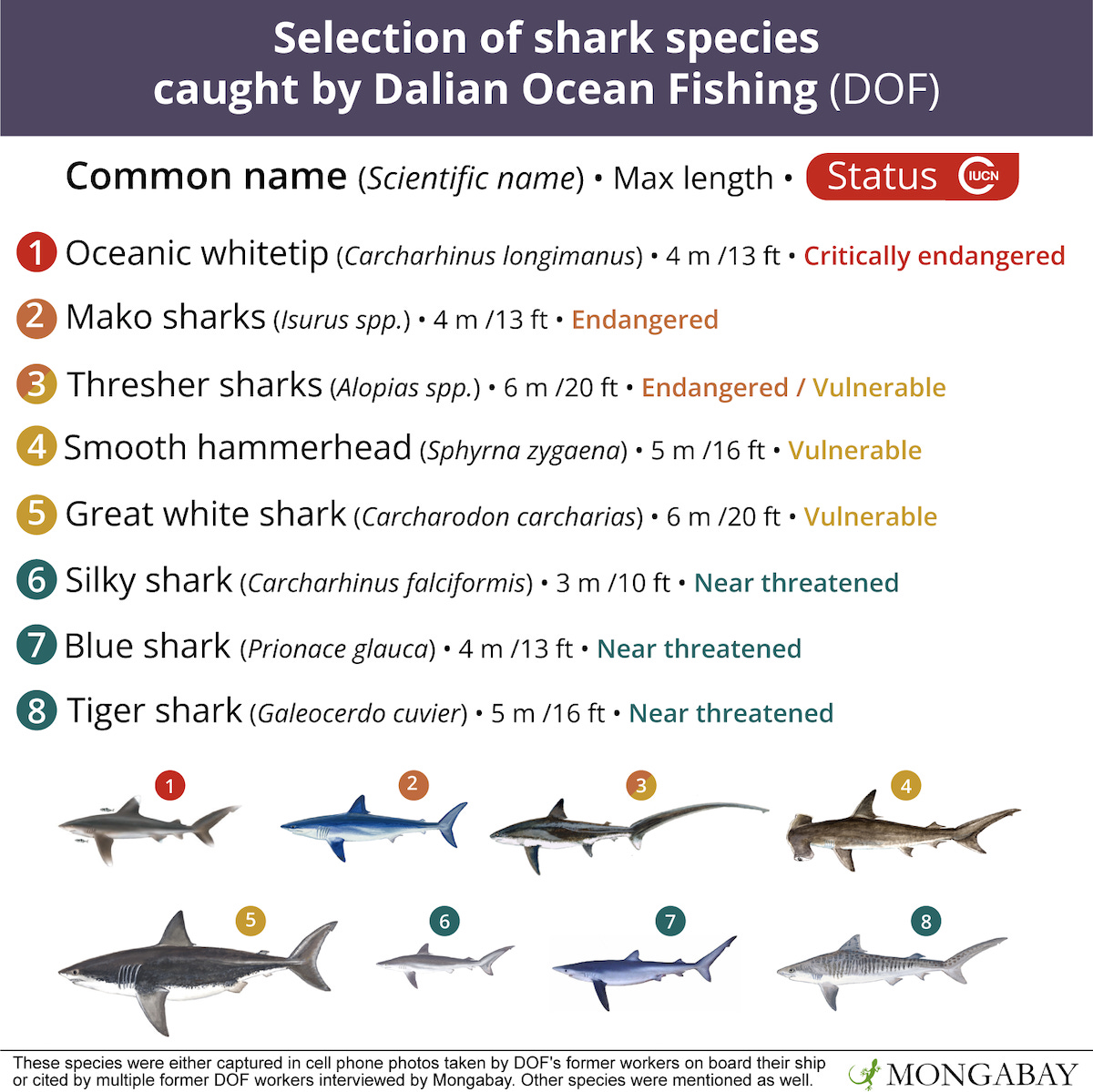

At present, China is the biggest culprit of illegal shark finning. Their absence from the UN’s list of the top 20 shark-fishing nations ultimately gave away their illegal trade as they have the most fishing boats and consume the most shark fin. A recent operation uncovered that the Chinese fishing company Dalian Ocean Fishing have been using banned fishing gear to deliberately catch sharks. Just five of the company's mass of longline boats had 5.1 tonnes of dried shark fin stored onboard in 2019 which is more than the total declared catch for China’s entire longline fleet in that area. All in all, a disaster for shark conservation.

Rachel Hopkins of The Pew Charitable Trusts said it best: “(This risks) sustainability, threatens scientists’ understanding of the status of shark populations, and puts responsible fishing operations at a competitive disadvantage.”

It’s not just China who is to blame either as the EU also plays a major role in the global shark fin trade, responsible for 188,368 tonnes of shark-fin products exported to Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan across a 17 year period.

But illegally obtained or not, shark finning is common practice in China as it secures the vital ingredient for shark-fin soup. I could make a joke and say it wouldn’t be shark fin soup without it, but they are actually so bland that chicken stock is added to the soup anyway. There’s also a risk of mercury poisoning, what with sharks being at the top of the food chain on a strictly fish-diet. Even without this awful trade, sharks would be at risk from overfishing, as demand for their meat and by products rise.

As an apex predator sharks are critical to the survival of ocean ecosystems. Maintaining balance, their mere presence spooks sea turtles away from seagrass meadows and stops smaller predators from munching on too much of the algae that allows coral reefs to thrive. So their slightly frightening appearance is actually a win for us, as animals are deterred from overfeeding on the underwater plants which sequester large amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere!

So what can be done to stop it?

Conservationists have fought for an outright ban on shark lines and wire leaders but have so far been rejected. It is currently only illegal to use this gear simultaneously which is an easy rule for fisheries to sidestep. The ban will be proposed again at the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) on 28th November 2022. Experts argue that to effectively stop the shark fin trade governments also need to enforce an increase in observers onboard, better in-port and at-sea inspections, and the use of the coast guard for at-sea patrols of fishing vessels.

The operators of a fisheries shipping fleet and the governments that permit their operation, are ultimately responsible for the continuation of the shark fin trade. Governments need to attain greater control through the suppression of the loopholes in their marine regulations and ensure catch is accurately reported. The US Shark Conservation Act 2010 enforces a ban on shark finning as all sharks must be landed with their fins intact, this prohibits back-alley deals and allows accurate data to be collected on shark species and their population levels. Policies like this, known as Fins Naturally Attached (FNA) policies, combined with tighter government controls on the fisheries sector is the simplest way to put an end to the shark fin trade. The overfishing of sharks may be allowed to persist under these particular regulations but the mass slaughter will be significantly reduced with stronger at-sea and in-port mandates on finning.

Very recently some positive news was announced in the fight to protect sharks. The 19th Conference (CoP19) of the Convention on International Trade in the Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) voted to upgrade 54 species of requiem and hammerhead sharks to the CITES Appendix II. In English, this means nearly all of the shark species who are murdered in oceans around the world for their fins are considered “not necessarily now threatened with extinction but may become so unless trade is closely controlled.” Hopefully this will drive stronger global protection for the sharks who need it, as only sustainable catch will henceforth be legal.

Changing how sharks are managed and protected is the only way to end the shark fin trade. But correcting our negative attitude towards them might help to speed the process up a bit. 100 million sharks are killed by humans every year whilst only 5 humans are killed by sharks every year.

Sharks are intelligent, inquisitive creatures who would much rather eat a juicy seal. Whether the negative connotations that surround sharks is the reason they’ve been subjected to such brutishness is up for debate but our narrative of them as mindless eating machines does more damage than we know.

Here at Beached we are building a community that can put our brains and resources together to highlight and fund solutions to the problems facing sharks and the oceans they live in. I hope you’ll join our humble community and click subscribe for free or support our work by purchasing the paid subscription.

All Beached posts are free to read but if you can we ask you to support our work through a paid subscription. These directly support the work of Beached and allow us to engage in more conversations with experts in the field of marine conservation and spend more time researching a wider breadth of topics for the newsletters. Paid subscriptions allow us to dedicate more time and effort to creating a community and provide the space for stakeholders to come together, stay abreast of each other’s work and foster improved collaboration and coordination.

One day Beached hope to donate a large percentage of the revenue from paid subscriptions to marine conservation organisations and charities to support their work too. Working together, we can reverse the degradation of our oceans.

Amie 🐋